We’ve compiled the top 6 environmental films for beginners. Are you an environmentalist looking for something new to watch? Writing an essay on climate change and don’t want to do any proper research? Having a movie date with your eco-friendly significant other? Looking to improve your knowledge of eco-inspired cinema? All of the above? Look no further.

First off, a quick tip; don’t put on The Day After Tomorrow.

PRINCESS MONONOKE (1997), dir. by Hayao Miyazaki

Possibly the best film to come out of Studio Ghibli until Spirited Away stole the limelight. The tale of hotheaded San, (the eponymous Princess Mononoke – Mononoke roughly meaning ‘vengeful spirit’ – which in this case is true), and reticent prince Ashitaka may not seem like an environmental film at first glance – a film filled with magic and spirits – who take the form of thinking, speaking animals, or ‘Forest Gods’, protecting the land they are a part of. San herself was taken in by the wolf god Moro as a child, and rides her similarly massive pups into battle with the leader of the nearby Iron Town, Lady Eboshi.

Princess Mononoke itself is constructed from a tangled web of interconnected themes, voiced expertly by a set of characters that each get their own specific screen time, thoughts, and narrative. This allows the viewer’s allegiances to change with every new line. Essentially, the workers of Iron Town want to tame and ‘destroy’ the forest gods, which will allow them to mine iron and produce capital with no interference – something the forest gods are, quite obviously, not happy about. Meanwhile Ashitaka, who at the beginning of the film fights with a demon boar and is cursed because of it, simultaneously searches for a cure for his curse while trying to create peace between the warring factions.

The most evident and overarching theme is that of progress vs. conservation – how does a human community survive, thrive, and improve it’s technological prowess without hurting the environment it exploits to further that progress? That question is only half answered in a very roundabout way – after the Forest Spirit gets it’s head severed from it’s body, spewing toxic sentient goo over the whole forest which kills everything it touches, the humans decide they need to rethink their relationship with the thing which ultimately gives them life: Life itself.

It’s beautifully written, funny and sad in equal measures, has some of most insanely gorgeous artistry of any Ghibli film, and has a wonderfully-strong female lead, and a male lead who doesn’t muscle in, acting as a stirring vision of calm masculinity (even if he has a demonic arm). Also, and this may seem controversial, but if you’re not a Japanese speaker, we prefer the dubbed version, with stellar voice acting from Claire Danes, Billy Crudup, Billy Bob Thornton, and Minnie Driver. The subtitled version is good, but the translated lines of the dubbed version evoke a lot more beauty.

BEFORE THE FLOOD (2016) dir. by Fisher Stevens

Actor-turned-environmentalist Leonardo Dicaprio heads up this 96 minute long environmental documentary. Fresh-faced but still bearded from filming The Revenant in 2015, DiCaprio presents the devastating impacts of climate change as they are happening, questioning as he goes humanity’s ability to reverse arguable the biggest problem we have ever faced.

The reason we add this film to the list is because of the impact DiCaprio has as both an auteur and a hollywood A-lister – who else do you think would have been able to interview both Barack Obama and the Pope in single film? Not us. Not through lack of experience we must add, but simply because DiCaprio’s name bears weight.

The film itself does not present much by the way of resolutions to the issues we face, but does a great job of visualising these issues. The film is shot over a period of three years, as DiCaprio talks to activists and dignitaries alike, from Greenland to the USA to Kiribati. He translates the complex scientific issues into easily-digestible bites, which through the film’s tone, sincerity, and cinematography, retain some of their actual bite.

The film itself isn’t groundbreaking and the choppy, Hollywood-esque cuts sometimes distract you from forming an emotional connection to what is on screen, or from receiving a suckerpunch of eco-anxious revelation. It has a few scenes that are definitely noteworthy, such as the conversation with astronaut Dr. Piers Sellers, and does a good job at providing bite-size morsels that present a much bigger, bleaker picture. A good film for beginners.

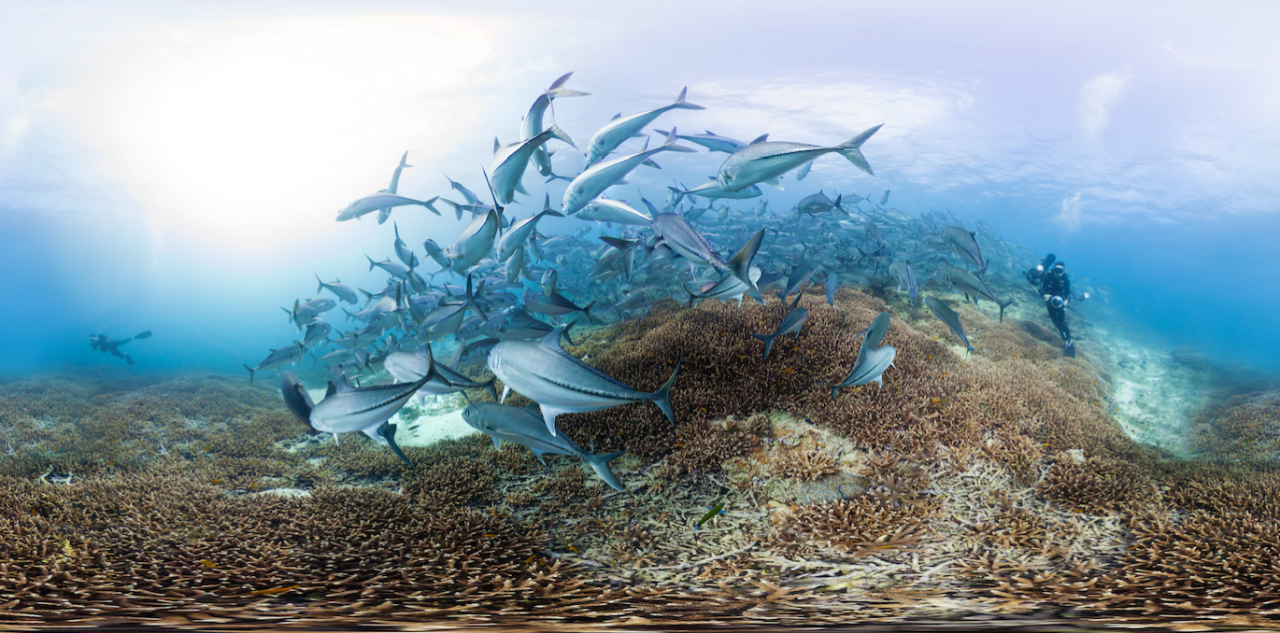

CHASING CORAL (2017) dir. Jeff Orlowski

Coral reefs. They occupy less than 1% of the Earth’s oceanic area, but provide a home for at least a quarter of all marine animals. They are also dying. Jeff Orlowski’s Chasing Coral sees a group of divers, scientists, and photographers from across the globe attempt to document this loss.

It’s a truly remarkable thing to see, timelapses of coral bleaching, dying, and decaying. We wouldn’t recommend this film for the date, it can be a little bleak at times. Yet, this is where Chasing Coral succeeds – it does a grand job of melting together voices, emotions, and hard facts.

Essentially, the oceans are the biggest heat traps and always have been, and as global temperatures rise the oceans get warmer and warmer. Coral, which acts as a home for some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, is very suited to particular temperatures. As the seawater warms, the corals bleach. This is a stress response, meaning that the corals eject all of the microscopic plant-life that gives them their colour, causing them to go bright white. The corals can sometimes survive in this situation, but the plant-life acts as their main source of nutrition, and more often then not, this bleaching will eventually lead to death.

Chasing Corals is a well-shot, well-paced film. It lacks in breadth, which is not an inherently bad thing. Too often environmental films try to focus on ‘all’ the issues, ending up lacking in crucial evidence. Furthermore, this can also help to overwhelm and alienate the viewer, presenting environmental issues as insurmountable problems. In its sole on the issue of coral, this film succeeds in presenting a well-rounded approach on a singular focus.

THE TRUE COST (2015) dir. by Andrew Morgan

Not simply an environmental documentary, The True Cost also looks into the social aspects of fast fashion; the exploitation, the consumerism, and how it all fits into global capitalism. This isn’t a tale of groundbreaking designers or fabulous models, it’s a documentary on the very beginnings of commodified and damaging haute couture.

Director Andrew Morgan was drawn to the subject after the Dhaka building collapse in 2013, where a commercial building in Bangladesh crumbled and killed over a thousand workers. These workers had been subjected to unsafe working conditions, and we’re also part of a business that manufactured for big brands such as Prada, Gucci, and Versace amongst others.

The film explores the structural poverty that comes with the fast fashion industry, looking at the unsafe conditions many workers face and how the environmental cost of the industry affects poor communities, further hinting at issues of institutionalised and environmental racism.

One of the most poignant and shocking parts of the film focuses on Indian-grown cotton. Demand for the crop led to the planting of genetically-modified cotton by larger companies, pushing the price up, leading to a number of suicides by smaller, traditional cotton farmers. The GM crops themselves needed more pesticides, leading to ecosystem damage and birth defects amongst newborns in the local Punjab population.

The main themes that run through the film are of exploitation and disposability – and not simply disposability of fashion, throwing away a top after a few wears – we are talking about the disposability of human lives and environmental security. To engage with this film is to realise that there is something truly wrong with where we source the very shirts on our collective backs. You may have spent £25 on it, but what is the true cost?

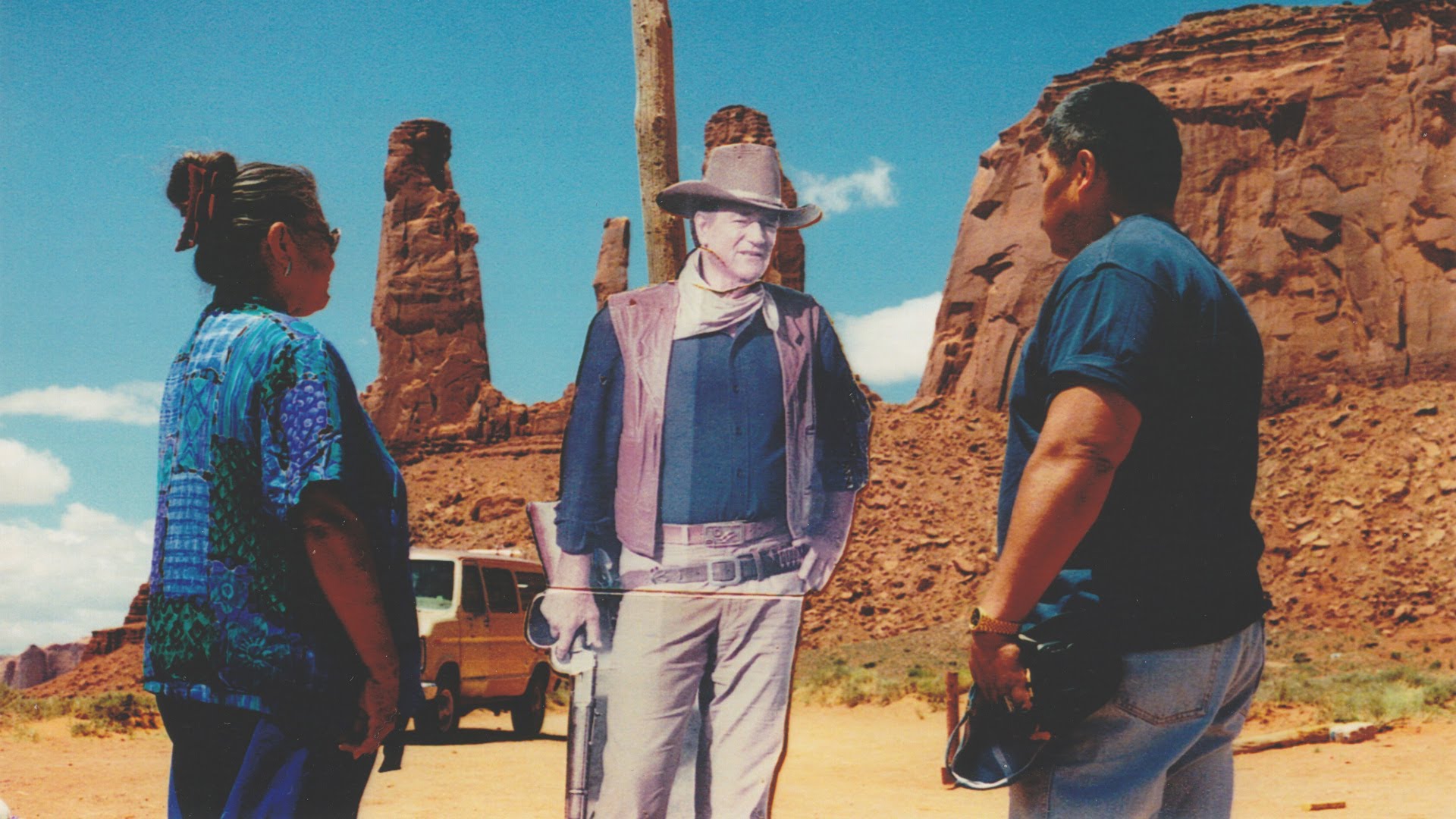

THE RETURN OF NAVAJO BOY (2000) dir. by Jeff Spitz

Released in 2000, The Return of Navajo Boy deals with an incredibly important, but unfortunately little spoken- about issue in the modern environmentalism movement. That is the issue of environmental racism.

Environmental racism is essentially a concept that explores environmental injustices that are carried out, either through practice or through policy, with a racialised context. Think of the American Bison, who were hunted to near extinction in the 1870s by the American army in an effort to force Native Americans off of their homelands.

In the context of The Return of Navajo Boy, we see the story of the Cly family, through them exploring the unregulated mining of uraniam in Monument Valley, Utah, and how it has caused illness. It raises key issues of white supremacy, political representation, and reparation denial, all within the context of environmentally-unfriendly policy. It is a film steeped in sadness, and a must-watch.

KOYAANISQATSI (1982) dir. by Godfrey Reggio

The word ‘Koyaanisqatsi’ is a Hopi word that roughly translates to ‘life of moral corruption or turmoil’. It’s a phrase that should be on the viewer’s mind while watching.

The film is the most experimental and ephemeral of those on this list and is more art than documentary. It is an 86 minute-long visual tone poem, consisting of slow-motion or timelapse imagery of cities and landscapes across the United States. If there was ever a film to convince us of Timothy Morton’s philosophical view of ecology and environmentalism, that humans need to be convinced that they live ‘inside’ climate change, rather than climate change being something that is in ‘another place’, this is it.

It’s essentially an instrumental piece. There is no dialogue to be heard, save for choral chanting in Hopi. The music is a score by American composer Philip Glass. Explaining the choice of no dialogue, director Godfrey Reggio said, “it’s not for lack of love of the language that these films have no words. It’s because, from my point of view, our language is in a state of vast humiliation. It no longer describes the world in which we live.” Eat your heart out Timothy Morton.

Reggio said of the film that “it is up [to] the viewer to take for himself/herself what it is that [the film] means.”, adding that “these films have never been about the effect of technology, of industry on people. It’s been that everyone: politics, education, things of the financial structure, the nation state structure, language, the culture, religion, all of that exists within the host of technology. So it’s not the effect of, it’s that everything exists within [technology]. It’s not that we use technology, we live technology. Technology has become as ubiquitous as the air we breathe …”

The film ends with a translation of three Hopi prophecies, which are chanted in their original language earlier in the film, the most poignant of which reads: “A container of ashes might one day be thrown from the sky, which could burn the land and boil the oceans.”

Maybe not the best film for a date.

SPECIAL MENTIONS

Into The Wild (2007), Interstellar (2014), Minimalism (2016), The 11th Hour (2007), Chasing Ice (2012), Climate Refugees (2010), Cowspiracy (2014), Under The Dome (2015), Erin Brockovich (2000), Silent Running (1972), WALL-E (2008), Pom Poko (1994), Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind (1984).